Aristotle and the Good Life

Aristotle's ethics is an ethics of the good life. How does one achieve the good life? In order to answer this question, we must have some understanding of what is meant by "the good". We begin with a description of "the good" as it is commonly understood by most of us. We speak of a good pen, a good computer, a good pair of skates, a good car, a lousy car, a lousy computer, etc. If we look very carefully, the good is directly linked to a thing's operation. When a thing has a proper operation, the good of the thing and its well being consist in that operation. The proper operation of a pen is to write, and so a good pen writes well. The proper operation of a knife is to cut food, so a good knife will cut well. The proper operation of a car is to drive efficiently, safely, smoothly, etc. So, a good car is one that drives well, that is, efficiently, safely, smoothly, etc.

Now, a thing operates according to its nature. We know that vegetative life exhibits the activity of growth, reproduction, and nutrition. It is of the nature of a plant to grow, reproduce, and nourish itself. A good plant will be one that does this fully. Thus, it will look healthy and strong. An animal, on the contrary, is more than a plant. It has more power or powers. Specifically, an animal has the powers of sense knowledge (external and internal sensation) and the powers of sense appetite (concupiscible and irascible), as well as the power of locomotion. So, it is not enough for an animal to be able to grow, reproduce, and eat. A good animal will be one that functions according to its nature. Hence, a good animal will sense well, be able to move well, have a healthy appetite, etc. A good dog has acute senses, runs and fetches sticks, eats well, etc. Man, though, is much more than a brute animal. Man is specifically different than a brute in that he has the specific powers of intelligence (the ability to apprehend essences) and will (desiring not merely sensible goods, but intelligible goods, such as truth, life, beauty, leisure, friendships, integrity, religion, marriage). So, it is not enough that human beings sense well, run fast, and eat the right foods, etc. A good man is one who functions according to his nature, which is a rational nature. Hence, a good man is one who reasons well and chooses well.

A Note on Happiness

Aristotle said that every agent acts for an end. The ultimate end sought in every one of our actions is happiness. As Socrates knew so well, all men desire happiness. But the question is what exactly constitutes a happy life?

Earlier we wondered whether or not it is possible to achieve everything that one has set out to achieve in life and in the end find oneself unhappy. The facts suggest that it is indeed possible for such a one to find himself unhappy. If this is true, then it follows that happiness is not necessarily doing what you want to do. That is a very striking point, if you think about it. It means that I am aware that I want happiness, and I have no choice in the matter, and yet what I think I want in life may not be what I want at all.

Is it possible to have a wife/husband, children, house, and a good job, and at the same time still be unhappy. Many of us have the intuition that yes, it is possible for such a one to find himself unhappy. If this is true, then it follows logically that happiness is not necessarily having a wife/husband, children, house, and a good job, etc.

Happiness, for Aristotle, is not something that comes to us from the outside. Rather, happiness is an inside job. Happiness is an activity, not a passivity, that is, it is not something that happens to you or comes to you from without. It is an activity rooted in human choices. In other words, if someone is unhappy, it is because he has not chosen well. And if one is happy, it is only because he has chosen well. Remember, a good man is one who reasons well and chooses well. Hence, a good man is a happy man. Happiness, according to Aristotle, is going to result from making choices that promote the fullness of oneÕs nature. Now human nature has specific powers, namely, intellect, will, and the concupiscible and irascible appetites. And so human happiness is going to lie in the perfection or right ordering of those human powers.

These particular powers of the soul are perfected by habits, obviously good habits. A good habit is a virtue, while a bad habit is a vice. Thus, happiness is activity in accordance with perfect virtue. Now virtue is two-fold: intellectual virtue (wisdom, science, understanding of first principles) and moral virtue (prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance). Moral virtues are habits that make their possessor morally good. Intellectual virtues, on the other hand, do not make a person morally good, but wise, or knowledgeable, or learned.

Contemplation

Happiness is the fulfillment of one's nature. But the highest power that renders us specifically different from brute animals is intelligence, that is, the ability to reason and know. And so human perfection will consist in the perfection of the intellect. As Aristotle writes: "All men by nature desire to know...For it is because of their wonder that men both now begin to philosophize and at first began to philosophize." The purpose of man's life consists in perfecting this sense of wonder. In other words, man's chief end in life, according to Aristotle, is to possess or contemplate truth, that is, to contemplate the highest things. The activity of contemplation is the highest activity in which a human person can engage. Consider the following words of Aristotle:

...the activity of our intelligence constitutes the complete happiness of man,... So if it is true that intelligence is divine in comparison with man, then a life guided by intelligence is divine in comparison with human life. We must not follow those who advise us to have human thoughts, since we are only men, and mortal thoughts, as mortals should; on the contrary, we should try to become immortal as far as that is possible and do our utmost to live in accordance with what is highest in us.

This is a remarkable idea. What Aristotle is exhorting us to do is to aspire after what is higher than us, namely truth. But note how many people in our society choose not aspire to what is higher, but pursue what is lower. Note the current preoccupation is genitalia in our culture. Consider how many shows and commercials are filled with sexual innuendo, as if the only purpose in life is to achieve the perfect orgasm. The genitals are located below the waistline, and so most people are living for what is below, not above. Aristotle points out that our happiness lies in striving to be "immortal as far as that is possible", in other words, to emulate the gods.

The believing Catholic or Muslim is able to see, though, that what Aristotle says is more true than he originally realized. We are immortal, as St. Thomas Aquinas will demonstrate. And so we really can strive to live like the angels, who eternally contemplate the beauty of God as He is in Himself. Indeed we must strive after immortality; for our destiny is know the highest being, which is God, and to contemplate the divine nature for all eternity.

But man is not an angel, that is, a pure spirit. Man is a rational animal (a psychosomatic unity). He has a host of powers in common with brutes. This is where difficulties of the moral life come into play. Man has to contend with two sensitive appetites, namely the concupiscible and irascible appetites. The concupiscible power has as its object a sensible good simply apprehended as such, i.e., a steak or a cold drink. Often, however, we experience difficulty in achieving a good (the steak is very expensive). The good then becomes a difficult good, and it is this difficult or arduous good that is the object of the irascible appetite. The concupiscible appetite gives rise to the emotions of love, desire, complacency, hate, aversion, and sadness; while the irascible appetite gives rise to the emotions of hope, despair, daring, fear, and anger.

Order vs. Disorder

Now sometimes the appetites rebel against reason. But man, if he is to be fully a man, must act in accordance with reason, that is, in accordance with what is highest in him. Sometimes a person might give up easily when things become difficult, or he might run when there is danger. Sometimes a person cannot hold a job because he has no self-control over alcoholic drink, or he has no control over his sexual appetite, and so can think of nothing other than sex. The appetites, if they are not controlled, can wreak havoc in our lives. They can move us to do irrational things. In short, the appetites can keep up from aspiring to what is higher and loftier.

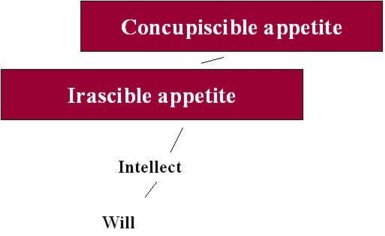

The good life begins by bringing order to one's life. A good life is an ordered life. In fact, peace is precisely an ordered life. The Latin word for peace is pax, which means order or harmony. The good life begins by bringing about harmony between the appetites and reason. The following is an illustration of what a disordered life looks like:

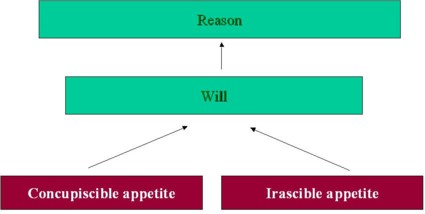

Note that the concupiscible and irascible appetites rule over intellect and will. Such people are governed by their feelings, or by their appetites. To live a disordered life is to live like the brutes. It is a life that is more bestial than it is human. A fully human life is one that is governed by reason. Note the following illustration:

It takes a great deal of work to order your life in accordance with reason, but this is precisely the key to a life of peace, that is, a happy life. The person who is governed by his appetites never finds peace, but is always restless and swayed this way and that, like a dry leaf on a windy day.

The Kalon

What does an ordered life look like? It looks beautiful. Note the order and harmony in a beautiful work of art. A person who has brought order to his life is one who is noble of character. Now the purpose of moral reflection is to determine the kalon, that is, the morally right, or the noble. "Morally right" does not seem to fully translate the kalon as Aristotle understood it. The kalon is the morally good, or the morally beautiful, that is, the noble. Some actions are noble, others are ignoble. The morally good person will choose what is most noble, that is, he will choose in accordance with reason (with what is highest in us).

Note that by virtue of the unity that exists between soul and body (matter and form), the morally beautiful character will become physically attractive. He or she will have an attractive or beautiful face. The converse is also true. A person of bad or ignoble character will not appear attractive for very long. It is not true that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, rather, beauty is in the eyes of the one we behold.

The happy man is the noble man. The reason this is true is that we can only bring order to our lives by perfecting the four principal powers of the soul that are open to perfection (intellect, will, concupiscible and irascible powers), and these powers are perfected by the four principle or cardinal virtues. The intellect is perfected by the virtue of prudence, the will is perfected by the virtue of justice, the irascible appetite is perfected by the virtue of fortitude (courage), and the concupiscible appetite is perfected by temperance. Prudence is the virtue by which we order our actions to their proper end, which is to be in accordance with reason. An imprudent man does not know what actions are in accordance with reason. For example, if he experiences anger, he will simply act on it and likely bring about a great deal of harm to others. An imprudent man does not know what the just course of action really is. He does not understand justice. He will lack the rest of the virtues, which is why Aristotle refers to prudence as the mother of all the virtues. Justice is in the will and is the constant will to render to another his due. Fortitude is the virtue that moderates the emotions of fear and daring. The brave man is not the person on Fear Factor who is willing to dive into a pool filled with poisonous snakes (that is boldness, not courage), or jump from one speeding boat to another. Rather, fortitude is the virtue that binds the will to the good of reason in the face of the greatest evils. There is nothing reasonable about swimming with snakes or risking one's life unnecessarily in order to prove oneself. But there is something reasonable and noble about going into a burning building in order to save someone's life. And finally, temperance is the virtue that moderates, in accordance with reason, the pleasures of touch. The most intense pleasures that need moderating are those associated with eating, drinking, and sexual activity. Abstinence moderates the pleasures of eating, sobriety is the virtue that moderates the pleasures of alcoholic drink, and chastity moderates the sexual appetite, ordering it to its proper ends, which are the procreation of new life, and the expression of marital love.

What Aristotle argues here is really, when you think about it, more in accordance with the facts. Recall the questions we asked earlier about whether being happy is necessarily the result of having a spouse, house, good job, etc.,. For only a virtuous person will be able to be a good husband/wife, a good parent, and a person committed to the good of the state. And so it is not enough to have these things in order to be happy. And it isnÕt doing what you want that renders a person happy, but willing the good, the noble, the beautiful. For it is impossible for a virtuous person (character) to be unhappy.

The Secondary Instances of the Kalon

The good life also includes secondary aspects that add to the happy life. Many people today confuse the secondary instances of the kalon with the primary, which is virtue. But happiness is found in virtue, not in these secondary instances, which only add to it, as salt adds flavor to food that is already good. These secondary instances include pleasure, good health and appearance, proper nourishment and sustenance, a full life span, friendships, sufficient wealth and enough time for leisure, and respectable family origin.

Finally, Aristotle underscores the importance of a proper upbringing. A child that is brought up well is well disposed towards goodness. It does not mean that he or she will necessarily turn out well. But a child that is habituated towards sense pleasure will mistakenly think that the purpose of his life is nothing but pleasure, which is a false notion of happiness. And a child that is habituated towards a quest for fame and power will mistakenly regard honors as the chief end or purpose of human life, or the principal means of happiness. But the pursuit of honors is fickle, and those people who are satisfied with the recognition of excellence rather than the excellence itself are deceived. Only a person brought up properly will recognize the kalon in the virtuous activity of the noble person. So it is true that good parenting does incalculable good. In fact, one could argue that in this light, parenting is probably the most important work in the maintenance of civilization.

Next Page:

Chapter 14: More First Principles

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13, 14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26

Article copyrights are held solely by author.

[ Japan-Lifeissues.net ] [ OMI Japan/Korea ]