Hospice vs. Palliative Care vs. Patients and Families who Choose Life

Rene Henry Gracida, Bishop Emeritus of Corpus Christi, Texas, hosts a blog that is a treasure chest of religious, political and philosophical gems. You can read his brief biography (here), and a little about his World War II Army Air Corps service (here). The video of his 50th jubilee homily (link here) is inspiring.

HOWEVER, this post isn't about Bishop Gracida. It is about two of his guest bloggers and their rousing debate a few weeks ago on the subject of hospice versus "palliative care."

Father Angelo, a priest with over a decade of experience caring for dying patients, was somewhat critical of palliative care. Ralph Capone, MD, medical director of the palliative care consultation service for University of Pittsburgh Medical Center-McKeesport Hospital, shot back defending "authentic" palliative care as defined by the Center for Palliative Care (CAPC; pronounced "cap-see"). Dr. Capone suggested that patients and families just need to do a little homework to find the palliative care teams that honor sanctity of life as opposed to a quality-of-life ethic.

I have a few thoughts concerning Dr. Capone's comments.

Patients live longer. Really?

Dr. Capone contends that patients live longer with palliative care as opposed to traditional medicine, and cites a study by Temel et al. to defend his argument. There are a few problems in citing that report. First, the study was limited to cancer patients; it says nothing about a multitude of other end-of-life scenarios and diseases. Second, the researchers studied only a relative handful of patients at one site; it is questionable whether that sample is representative of the entire country. Even if the sample was representative, patients who are flagged for palliative care generally have a multitude of comorbidities, and the variability of those individual patients makes it difficult to make categorical assumptions. Third, I can cite at least one other study that suggests just the opposite; that palliative care results in shorter life. (Brumley et al., 2007)

Euthanasia, stealth and otherwise.

With regard to euthanasia: Dr. Capone asserts that euthanasia is more likely in hospice than in palliative care outside of hospice, and he narrows the definition of euthanasia to what he calls "stealth euthanasia:" overdosing and terminal sedation (sedation while withholding nutrition and hydration). He and Julie Grimstad, writing in Ethics and Medics, attributed "stealth euthanasia" to Choice in Dying, Partnership for Caring, and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. They quoted Ira Byock, Joanne Lynn and Timothy Quill as examples. What they fail to mention is the fact that those people and organizations were part of the small group that defined palliative care as it is known today. Partnership for Caring (founded by Byock) formed the core of the little Steering Committee that wrote palliative care's Clinical Practice Guidelines. Most, if not all, of the 20-member Steering Committee were involved in Byock's "Promoting Excellence" projects. The Steering Committee was funded by the Mayday Fund whose executive director, Fenella Rouse, was fresh from her role as director of the Society for the Right-to-Die. At least half of the members were dependent on funding from Soros's Open Society Institute, and at least a quarter of the members were dependent on federal funding through the NIH.

However, Father Angelo wasn't talking about terminal sedation. He was talking about palliative care teams pushing patients into decisions regarding life-saving treatment. Although the palliative care community (CAPC and the like) is always eager to defend the so-called "constitutional right" to refuse treatment, for some reason it is AWOL when it comes to cases such as that of Terri Schiavo.

Almost more than pain management and sedative use, the "right to refuse treatment" was a central tenet for those who drafted the Clinical Practice Guidelines over a decade ago. Shortly before Choice in Dying rebranded itself as Partnership for Caring, and became the administrative home for the Steering Committee, it announced the remarkable discovery of a "Constitutional right" to refuse treatment, which it pledged to uphold:

An individual has a constitutional right to request the withdrawal or withholding of medical treatment, even if this procedure will result in the person's death. Honoring a person's right to refuse medical treatment, especially at the end of life, is the most widely practiced and widely accepted right to die policy in our society. . . .The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of honoring a refusal of treatment in the case of Nancy Cruzan in 1990.

Apparently there haven't been enough takers on that "right to refuse treatment" idea. Patients and families keep requesting life-saving treatment, so the focus has shifted to convincing families to forgo treatment for their loved ones. The "right to refuse treatment" is slowly morphing into a responsibility and duty to refuse medical treatment.

Consensus building - or bullying?

Dr. Capone leaves readers with the impression that Father Angelo's experience - seeing families pushed into palliative care and limits on life-saving treatment - is a rare or isolated experience. Not only is it not rare, it is planned and it is widespread. A 2011 Journal of Palliative Medicine article provides solid evidence. A decade after he helped draft the Clinical Practice Guidelines, Andrew Billings, MD, conducted an extensive literature review to prove that "family meetings in end-of-life care, especially when conducted prophylactically or proactively, have been shown to be effective procedures for improving family and staff satisfaction and even reducing resource utilization." [My emphasis. And my comment: Good for the staff; what about the patient?]

Among other things, the article makes two interesting points: before there can be consensus among family members, there must be consensus about goals among palliative care team members; and for palliative care, often the ultimate goal really is "less treatment." Billings provides a helpful table summarizing key points from a dozen articles indicating that interventional palliative care and ethics consultations resulted in less life-sustaining treatments, "reduced use of life-sustaining treatments in nonsurvivors," "reduced resource utilization after DNR," "reduced ICU length-of-stay after comfort care," and less "nonbeneficial resource use."

Keep an eye on subjective qualifiers such as "nonbeneficial" and "appropriate" (as in "appropriate treatment"). Dig deeper into those qualifiers and you'll find judgments on quality of life. Triggers for palliative care consultations, such as those found at the CAPC website (here), and in an article by Meier and Weissman, include quality of life indicators such as declining ADLs (activities of daily living), feeding-tube placement in cognitively disabled people, and even "multiple hospitalizations." Palliative care is recommended in all of these scenarios. But palliative care has multiple, morphing definitions. It is end-of-life care; it is not end-of-life care; it is curative treatment and it is not curative treatment; it is symptom management; it is consensus and conflict resolution; it is not prolonging death; it is not prolonging life; it is psychological counseling; it is sending the patient home for a comfortable, well-planned death. Which of the many palliative care definitions will be applied to the disabled or chronically ill patient with multiple complications and "multiple hospitalizations"?

This isn't the 1980s, and this isn't the medicine it once was.

Without a doubt there are many excellent, dedicated, pro-life palliative care doctors and nurses at the bedsides of patients all across the country. However, these good doctors and nurses simply have no idea the extent to which "palliative" - as they once knew it - has been changed on a grand national scale.

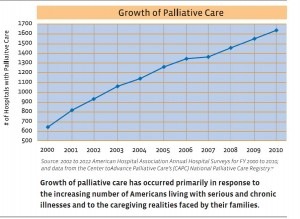

So when Dr. Capone suggests that patients should seek out a life-affirming palliative care program, you have to ask whether this is a realistic solution. First, you had better hope that you like the CAPC brand of palliative care, because 60% of hospitals with 50+ beds are using palliative care that is affiliated with CAPC. Moreover, as Father Angelo remarked, if you are extremely ill - sick enough to be in a hospital - you are hardly in a position to do a survey of alternative treatment centers. I'll add that many times there is no alternative at all, as indicated by a CAPC report that one out of six hospitals in the U.S is a sole community provider - meaning that the nearest alternate hospital is over 35 miles away. On top of that, 37% of those "sole providers" use palliative care, which means if you are in one of those hospitals, you're stuck with what you are given.

The medical landscape has changed dramatically since the 1980s when palliative care was synonymous with hospice, when "the right to refuse treatment" was a greater concern than being discharged from the hospital too early, and when the government wasn't openly discussing national health care rationing schemes to fix the shortage problems caused by its endless centralized planning, redistribution, and the toxic effects of meddling with payment methods. In such a context, one is well-advised to be skeptical of a referral to palliative care.

Article copyrights are held solely by author.

[ Japan-Lifeissues.net ] [ OMI Japan/Korea ]